Home Exhibitions MSVU Collection Publications Posters Working Title Resources

Home Exhibitions MSVU Collection Publications Posters Working Title Resources

|

Home » Publications » Catalogue Excerpts » Queer Commodity

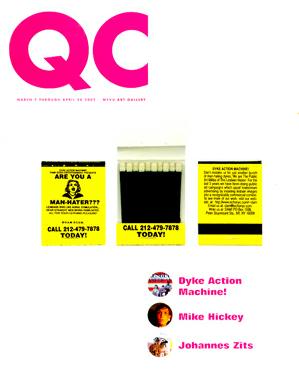

Queer Commodity   Purchase the catalogue Purchase the catalogueGo to the exhibition’s webpage... Grab your baskets, girls, we’re going shopping! What do you buy the queer who has everything? Rainbow teddybears with giant erections? Dildo kits with six different flavors of lube? Or for the particularly well-to-do, a south-seas cruise where what cruises is a lot more than the Love Boat? Yes, honeys, we are a target market. Our closets have become kiosks, our bath houses gift shops, our molly houses shopping malls. We have been assimilated into the very marketplace that used to (sometimes still does) deny us jobs and benefits. Nor has the transformation been merely material; it has heralded changes in the social construction of queerness as well. What used to be a “waste” in the spermatic economy — many out queers have pointedly had no interest in producing children — has been transformed into myths of disposable income; and the cliché that gay men are the arbiters of good taste has resulted in our becoming a sought-after market share. Straights know this truth about real estate: buy your house in the faggots’ ghetto; property values will only go up. And once you get there, befriend the local lesbian; who better to turn to when you need your gas barbecue assembled? In the eighteenth century we were defined by our acts, by the end of the nineteenth century we were defined by our desires, and now, in the early twenty-first century, we are defined by our commodities. And “commodity,” we should not forget, comes from the Latin word meaning “convenience” and “complaisance”: queer capitalism has become our self-definition and our central oxymoron, absorbing us into and erasing us from the culture in which we live. But is the idea of queer capitalism only one more oppressive ideology, or is there something we can gain from it? According to John D’Emilio, what we have gained from capitalism is the very idea of the homosexual identity that makes our critique possible. He argues that the advent of capitalism, which produced large urban centres, effectively dissolved the individual’s reliance on a family-based farming economy and forced many people to move to cities to find employment. In so doing, they could form groups based on common interests, including sex, making possible the whole notion of “gay and lesbian identity.” Michel Foucault would suggest much the same thing: the homosexual identity, he argues, can never be seen as a phenomenon outside hegemonic culture, but one that is necessary to — and enabled by — the discourses of the hegemonic culture. One can only be normal if one has something to be normal against, and one can only be different if there is a large group of sameness (homo?) to be different from. And it’s this very difference that market capitalism takes as its starting point. If I am different from you, then I want different things from you; and if I want different things from you, then you will have to produce them for me. Even if I don’t know I want them, you can tell me I do, which makes us both happy. Either way, I can never forget that who I am — and who you are — is impossible outside the economic nexus. Capitalism isn’t something for me to accept or reject; it is the system that makes “me” possible.

Let me push my argument one step further. My dictionary also tells me that commodities are “anything that one trades or deals in.” In gay and lesbian culture, what one trades or deals in (roughly or otherwise) is bodies. Bath houses, internet porn sites, chat rooms, strap-ons, the last waltz at your local gay bar: all make bodies into things that some interested shopper wants to consume for his or her pleasure. For free if possible, but for dollars if necessary. Sound distasteful? Good. It is precisely that sense of the distasteful that we might capitalize on (yep, pun intended) in our queer commodifying practices. The body-as-object is the body-for-pleasure. Unlike the body in the history of the marriage market, it is not necessarily the property of another, more powerful agent, as the body of the woman has been. Your queer body is an object of trade, but only momentarily; you get to take it home with you after it’s been given breakfast. Moreover, it’s a commodity unlike those others that are marshalled to the service of material productivity: if there’s one historical truth about queer sex, it’s that it is non-utilitarian, unproductive, useless for anything other than itself. It does not exist to produce something else; it is not (usually) a baby-making machine, nor is it a symbol, like the $10 bill, for something “real.” It gains no interest other than an erotic one — if you’re lucky, or have the right dresser. (Sorry, but as in the free market, there is no promise of democracy or equality in queer economies). If my breakfast companion and I are both consumers, who or what precisely is being consumed, besides breakfast? For that matter, if I spend an evening, or just twenty minutes, being consumed, is that necessarily such a bad thing? |